For his birthday, my youngest nephew received Goldilocks and the Three Dinosaurs:As Retold by Mo Willems. It looked like a hilarious story, and I had faith that anyone who could write Don't Let The Pigeon Drive the Bus could do great things for the retelling of the Goldilocks and Three Bears story. Under Mr. Willems' hand, Goldilocks goes from a tale of too big, too small, just right to a tale of carnivorous dinosaur intent. No wandering children are hurt in the telling of this tale, and my sister tells me there are giggles in her household when the new Goldilocks gets read, so I think the gift was a success.

Grazie mille, Mo Willems.

I share this information not to promote the books of Mr. Willems* but instead to talk about the concept of something--a bed, a chair or food--needing to be just right.

I think, in our day-to-day lives, Americans have learned to see food as something to be gobbled up to feed a hunger. Eating is practical. Food is our fuel. So perhaps it's a hunger like the dinosaur's carnivorous intent; we must EAT ALL THE THINGS. And when eating is emotional, it's about more than the practical hunger. Perhaps it's a hunger for convenience and speed; where appeasing the hunger is simply a necessary step on our way to bigger and better things. Perhaps it's a hunger for variety; in our land of plenty we have so very many things.

Whatever it is, we often consume food solely. We don't enjoy it. We don't savor it. We don't enjoy it.

Why would we? It's just a thing. It doesn't need to be just right because there's always more, and we come by it easy.

Yet easy doesn't even begin describe the way Italians see food and food preparation. I just spent two days in Italy's Food Valley, an area between the Alps and the Appenines along the Po River. There we visited the world's largest pasta production plant (courtesy of Barilla) before meeting with producers of some of Italy's D.O.P. delicacies like culatello (a type of ham), parmigiano-reggiano (real parmesan cheese) and aceto balsamico (real balsalmic vinegar).

Whether it's Barilla manufacturing 400,000 pounds of pasta a year on nine different lines or it's Hombre creating 12 rounds of parmigiano-reggiano a day, everything about the process must be just right.

Barilla only uses water round under unfarmed and untreated land. The quality of the water is critical because the pasta only contains two ingredients--water and durham wheat flour. Barilla buys its wheat directly and mills it on the site of the pasta production.

The parmigiano makers only use milk from Holstein cows fed a diet of only dry fodder, no fermented silage. They use a hammer to listen for sounds of air bubbles as the wheels of cheese dry and cure. An air bubble means aerobic activity is going on, and that is the end of wheel of cheese. It can no longer bear the mark of parmigiano-reggiano.

The culatello must be made from a pig that was raised in just the right place and is fed just the right things (including whey from the production of parmigiano-reggiano) before the pork butt can be bound in a pig's bladder and hung in a basement for at least 12 months to cure in humid air. (Prosciutto, on the other hand, if always the hind leg and is cured in dry air.)

But the winner of the just right sweepstakes are the acetaia. These are businesses that make traditional balsamic vinegar of Modena. The aceto (vinegar) is made of one ingredient (cooked must from white grapes), and it must age for a minimum of 12 years.

TWELVE YEARS.

Now that's a barrier to entry.

And a barrier to taste.

Food production, to Italians, is serious business because eating is serious, too. Lunch is the biggest meal of the day. It's a family affair, and it's meant to be shared, to be savored, to be enjoyed.

For me, at least, it changes the way you eat and the way you feel about eating when you know that the cheese-making process is longer than human gestation, when you know that it takes longer to develop a line of traditional aceto than it takes to complete compulsory public school education.

It's safe to say that I eat well in Italy. When the ingredients are so good, how can the act of eating go any differently?

Buon appetito!

*Which I'd gladly do, but that's a tangent.

I share this information not to promote the books of Mr. Willems* but instead to talk about the concept of something--a bed, a chair or food--needing to be just right.

I think, in our day-to-day lives, Americans have learned to see food as something to be gobbled up to feed a hunger. Eating is practical. Food is our fuel. So perhaps it's a hunger like the dinosaur's carnivorous intent; we must EAT ALL THE THINGS. And when eating is emotional, it's about more than the practical hunger. Perhaps it's a hunger for convenience and speed; where appeasing the hunger is simply a necessary step on our way to bigger and better things. Perhaps it's a hunger for variety; in our land of plenty we have so very many things.

Whatever it is, we often consume food solely. We don't enjoy it. We don't savor it. We don't enjoy it.

Why would we? It's just a thing. It doesn't need to be just right because there's always more, and we come by it easy.

|

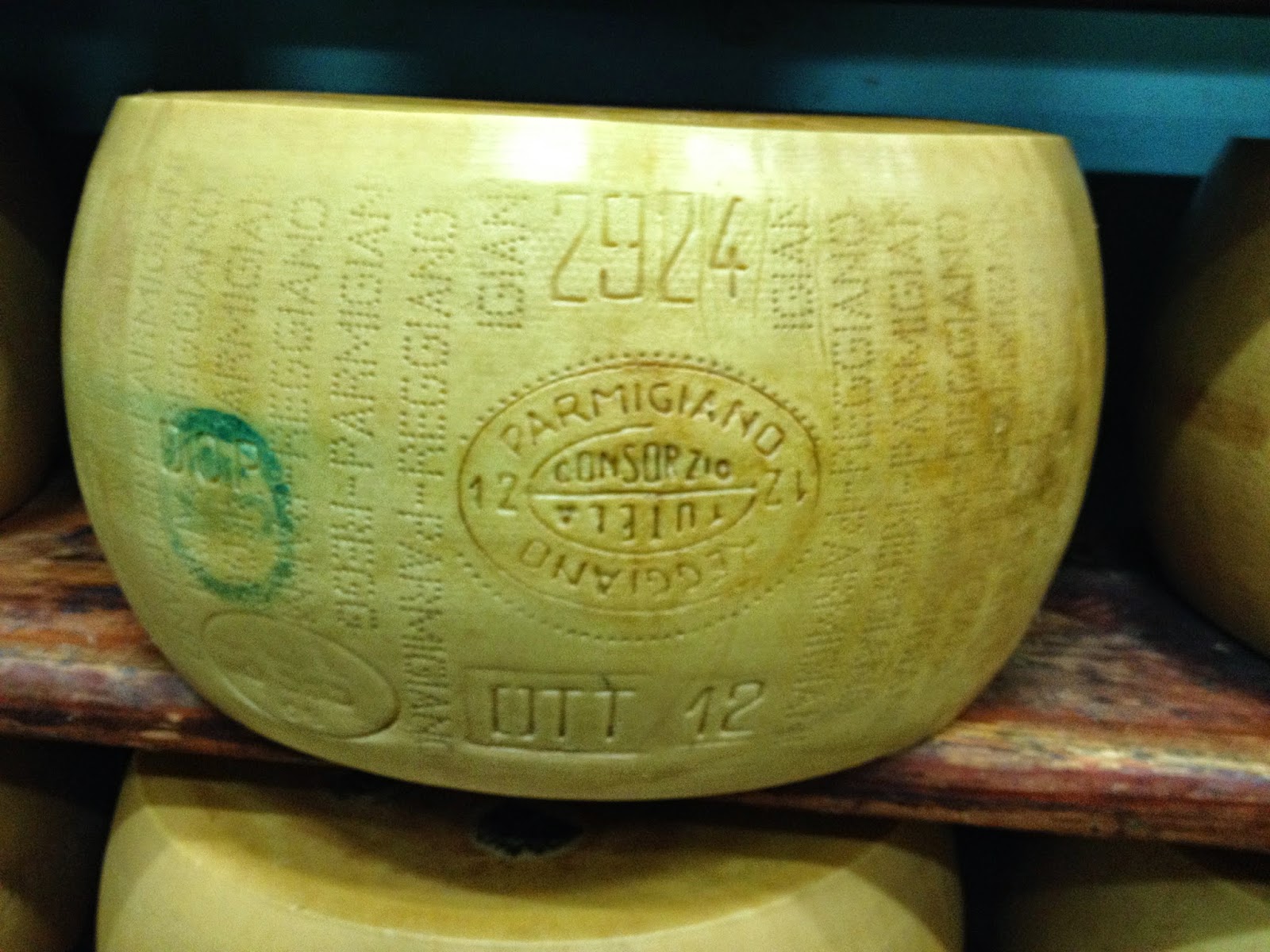

| This wheel of cheese started curing in October 2012. It's worth approximately 500 Euro. |

Yet easy doesn't even begin describe the way Italians see food and food preparation. I just spent two days in Italy's Food Valley, an area between the Alps and the Appenines along the Po River. There we visited the world's largest pasta production plant (courtesy of Barilla) before meeting with producers of some of Italy's D.O.P. delicacies like culatello (a type of ham), parmigiano-reggiano (real parmesan cheese) and aceto balsamico (real balsalmic vinegar).

Whether it's Barilla manufacturing 400,000 pounds of pasta a year on nine different lines or it's Hombre creating 12 rounds of parmigiano-reggiano a day, everything about the process must be just right.

Barilla only uses water round under unfarmed and untreated land. The quality of the water is critical because the pasta only contains two ingredients--water and durham wheat flour. Barilla buys its wheat directly and mills it on the site of the pasta production.

The parmigiano makers only use milk from Holstein cows fed a diet of only dry fodder, no fermented silage. They use a hammer to listen for sounds of air bubbles as the wheels of cheese dry and cure. An air bubble means aerobic activity is going on, and that is the end of wheel of cheese. It can no longer bear the mark of parmigiano-reggiano.

The culatello must be made from a pig that was raised in just the right place and is fed just the right things (including whey from the production of parmigiano-reggiano) before the pork butt can be bound in a pig's bladder and hung in a basement for at least 12 months to cure in humid air. (Prosciutto, on the other hand, if always the hind leg and is cured in dry air.)

|

| This is a third generation family run business. |

TWELVE YEARS.

|

| These lines of aceto were started in the early 1970s. You know, like me. |

Now that's a barrier to entry.

And a barrier to taste.

Food production, to Italians, is serious business because eating is serious, too. Lunch is the biggest meal of the day. It's a family affair, and it's meant to be shared, to be savored, to be enjoyed.

For me, at least, it changes the way you eat and the way you feel about eating when you know that the cheese-making process is longer than human gestation, when you know that it takes longer to develop a line of traditional aceto than it takes to complete compulsory public school education.

It's safe to say that I eat well in Italy. When the ingredients are so good, how can the act of eating go any differently?

Buon appetito!

*Which I'd gladly do, but that's a tangent.